Marc “Elvis” Priestley, host of the Discovery Channel’s Driving Wild

For the last year I’ve been working away behind the scenes with a very talented group of people from production company, Dragonfly Film and Television Productions and Discovery Networks International, to make a series of programs linked to travel, extreme engineering and my F1 experience.

I’ve explored the planet, visiting some of the most incredible places, meeting some amazing people and getting involved in spectacular types of motorsport.

Finally, after a lot of hard work, it’s ready and coming to the Discovery Channel around the world. It’ll be called either Gears, Grease and Glory, or Driving Wild, depending on which region you’re in.

Here’s a short taster…enjoy.

#GearsGreaseandGlory #DrivingWild

I don’t actually remember the first time I ever met Tyler, which is certainly no reflection on his stature with the team, more so of my ‘rabbit in headlights’ type existence in my first few weeks in my new dream job. When we were introduced though and people began relaying the stories and tales of his time at McLaren, it quickly became clear he was someone who had respect.

I don’t actually remember the first time I ever met Tyler, which is certainly no reflection on his stature with the team, more so of my ‘rabbit in headlights’ type existence in my first few weeks in my new dream job. When we were introduced though and people began relaying the stories and tales of his time at McLaren, it quickly became clear he was someone who had respect.

I can’t talk with too much credibility about the Tyler of the old days, I’m sure many of us have read the incredible tributes and obituaries, if not either of his two brilliant books. What I can do is talk about the Tyler I knew, the guy who inspired me, taught me, rolled his eyes over the top of his glasses at me when I did something stupid…again, and the the guy who made me laugh until I cried on regular occasions in amongst the high pressure, often chaotic, environment that was a Formula One race garage.

Tyler, or TJ, as he was known to most of us, was a hugely important figure in the history of our team. I can liken him to an elder statesman to whom the younger ones in our group, as I was once, would turn to for advice or just to hear a fascinating tale of what life used to be like for the Grand Prix mechanics of old. Figures like him are important in enclosed, insular worlds like the Formula One fraternity, much like tribal elders play a crucial role in being the much revered link between old and new, he was our own encyclopaedia of knowledge and experience.

Where TJ differed from many a man in his 60’s, as he was when I first encountered him, was that this incredibly fast moving, hi-tech world of F1 had far from passed him by and left him in a distant era. His role as Systems Engineer to Mika, Kimi, Fernando and others meant he worked at the cutting edge of the complex electronic and hydraulic technologies on the car, a side of things that, at times, baffled the hell out of me. Despite understanding them, he did still think the levels of complexity were ridiculously over the top and that real racing could be done from anywhere with a hammer and an adjustable spanner.

Everything he did though, he did with highly structured accuracy. Working to his own checklists, not allowing anything or anyone to move until he was ready. Checking, double and triple checking that everything was as it should be before the car was set up, fired up or even cleaned up.

I saw someone recently describe him as “the nicest grumpy bloke I knew”, which made me laugh. His disdain for anyone or anything that didn’t work properly, or to his liking, was well known. It was largely well known because when he went ‘off on one’ about something, the whole garage knew about it. It wasn’t so much that he would shout and scream, but more that everyone would stop what they were doing and listen to, what was almost certainly going to be, a hilarious rant.

It must be almost possible to collate a book from the sayings and phrases Tyler used to come up with when managing to so eloquently express his disgust or disbelief at certain situations. As I describe a few of these now, it’s important to try and read his quotes in the deep, gruff, slow, grumpy American twang that those who knew him remember so well.

One of my absolute favourites was from 2008, Lewis’ title deciding weekend. In the build up to the race the team had rightly decided the best way to approach the GP was not to change things, despite only needing to finish 5th to win. Inevitably over the weekend, amongst huge tension, engineers got nervous and changed some gearbox parts, thinking they’d be better. On Sunday morning, the guys on that car had gearbox issues during the engine fire up and a concerned crowd including Ron, Paddy Lowe, Pat Fry and others gathered around to desperately scratch heads.

– TJ walked up to me, peering over his glasses and shaking his head and said “You know what Elvis? You spend all year wiping your ass with one hand, half way through switch to wiping it with the other, it’s no wonder you’re gonna get shit on your thumb!” He turned and walked away and I watched his shoulders rise and fall as he was clearly chuckling to himself.

When the team moved into the hugely impressive McLaren Technology Centre with all it’s glitz and glamour a mile or so from our old factory, TJ was less than impressed. He just wanted to get on with racing and found the whole thing a distraction he could do without. He was a creature of habit and finding his way around the enormous new facility or waiting for a sensor to decide when you wanted to turn on the taps in the toilets, rather than him turning a handle when he was ready, frustrated the hell out of him for a while. I remember trying to fire up a car at MTC for the first time. A crowd of people gathered in attendance, we fitted the fancy new exhaust extractor unit emerging from the shiny tiled floor and it didn’t work. Health and Safety prevented us from starting the engine without it and Tyler became more and more annoyed until he burst.

– “Jesus fucking Christ! The only thing in this Goddam building that’s supposed to suck, doesn’t!” The race bays erupted into laughter and Tyler just shook his head in disbelief.

Sometimes the size of the modern team made things overly complicated in his view. Back in the day if something needed doing or a decision needed making he’d just get on and do it. So at one race, during a particularly lengthy discussion between a group of engineers and management over the intercom, about whether or not to fit wet tyres at the next pitstop, TJ just had to interject.

– “Jesus Christ here…why don’t you guys chuck a piece of string out the front of the Goddam garage, drag it back in, if it’s wet you need wet tyres…Jesus Christ.”

I could go on all day with his off the cuff sayings and reactions, but they’ll definitely keep me smiling for many years to come.

He was just a good guy who gave his heart and soul to win races. Some of my proudest moments at McLaren were as part of the close knit team that formed the crew for Kimi’s car between 2002 and 2006 and Tyler was very much a part of that. Him and I formed a close bond throughout that time and I looked up to him immensely. It’s not often in any line of work you get the opportunity to work with someone who’s such an endless resource of knowledge and unrivalled experience and also a great friend.

In late 2013 I was genuinely honoured that he, and his lovely partner Jane, made the effort to come to my wedding in East London. Shortly afterwards he fell seriously ill, which ultimately led to his incredibly sad passing. Despite not having seen him for a few months because of extensive work travel, I miss him already and will continue to do so.

There are definitely worse mottos to live life by than Tyler’s…

”It’s not that life is too short; it’s that death is too long. So best get on with things.”

Marc Priestley

People are always asking me how I got into Formula One in the first place and for any advice for them or their sons or daughters who might be eyeing up a similar career in the pitlane. To those who’ve approached me face to face, I always try and give the most in-depth and accurate description of my own experience and words of sincere encouragement for those who might like to follow in my footsteps. For the many who get in touch through Twitter or similar means, it becomes a lot more difficult to convey my genuine passion for the world of Formula One and the life that it becomes for those within it, in just 140 characters.

…so I thought I’d have a go here.

I grew up in a village in the UK, on the doorstep of Brands Hatch, which, during many of the formative years of my childhood hosted the British Grand Prix. I’ve no doubt that, even if subconsciously, that must be where the motor racing bug was contracted.

Friends of mine had a house whose garden backed onto the circuit perimeter and we’d regularly slip through a hole in the fence and into the woodland that lined the famous track. We had a wonderful and unique vantage point, albeit a touch on the dangerous side and more than once found ourselves bringing out the red flags as we were spotted crouching trackside and duly evicted by circuit officials. It was bad enough being responsible for bringing a test day or practice session to a halt as a truck was sent onto the circuit to pick us up, but even worse that they repeatedly threw us out at the main gate on the other side of the village, meaning a terribly long walk back to my mate’s house to collect our bikes.

Growing up with the sounds of motorsport in the air and the regular influx of international race fans and teams meant I was quickly hooked. I became fascinated by the workings of the sport and in particular, remember dreaming of what it must be like to be involved in those incredible pitstops.

When it came to making decisions about my career, despite having a serious passion for motorsport, there was never any advice to follow my dreams from school advisors or teachers, it was much more about knuckling down and getting the academic grades. The advice was to focus on the subjects I was doing well at in school and then see what I could do with them further down the line.

I duly followed the advice (for once) and began A-Levels in subjects that I was good at, but in truth wasn’t excited about in the slightest.

It’s certainly not that it was bad advice. For many people that would be a very sensible path to follow, even for some as a possible route into F1, it’s just that deep down I knew I had my heart set on working in motor racing and wanted to be hands on. Until I’d at least given that a try I would never be fully committed to anything else.

Half way through my A-Levels I plucked up the courage to speak out and was fortunate my parents were very supportive. I made the switch to study Motor Vehicle Engineering.

Combining studies with various work experience placements gave me my first taste of actual trackside motor racing AND I LOVED IT. Working voluntarily with a small race team gave me a real life insight into what it was like and there was no turning back from the very first time I set foot inside a circuit wearing a team shirt. I may’ve been doing little more than making tea and wheeling tyres around at this stage, but I was 100% convinced this was where I belonged.

This is where one of my biggest pieces of advice for young people comes in. Work Experience.

We generally only get one opportunity in our lives to work for free and that’s when we’re young. Take that chance. Offer your services to as many places of interest as you can possibly fit in. Try as many different types of motorsport as you can, as many different roles as you can. Write to as many companies as you can, show your passion, give up your spare time for it, make yourself stand out from the pile of CV’s on the team manger’s desk. In today’s world it doesn’t take a genius to decipher a company’s email address format and if you can find out the names of people in the key positions at various teams, you can get a personal email directly into their inbox, rather than the traditional generic CV sent through HR. Be creative, persistent and innovative, not only will it get you noticed, but they’re key traits for working in F1 and that’ll give an insight into your personality as well as the document itself.

Having never really left the village I’d grown up in, it was a very brave me that, after finding a contact through a neighbour, offered my services to a Formula Ford team based in Milton Keynes and was given the chance to spend two weeks with them during my summer holidays. I packed a bag and went to live with one of the mechanics for a fortnight and had the time of my life. I spent time preparing the cars, took them testing at the Mallory Park circuit and eventually got to join them for a race weekend back at Brands Hatch.

I did a good job, tried to be the best at whatever they asked me to do, was inquisitive and took in as much as I possibly could.

My mind was 100% set on a career in racing and I used my experience, albeit limited, to get an apprenticeship with a small team racing Caterham 7’s.

I had a clear goal of getting into Formula One, so worked my way up the ladder towards the top, all the time writing hopefully to F1 teams along the way. Every time I was at a race track with our little support series, I would seek out mechanics and engineers from the championships headlining the event, asking advice, making contacts.

The motor racing ‘ladder’ for single seater mechanics was much the same as it was for drivers back then, FFord, F3, F3000, culminating in F1. Coincidently, my path followed that of Jenson Button, moving into Formula Ford together and later onto British F3. Where he went straight from there into F1 with Williams, I persisted in constantly writing to every team and moved into Formula 3000 (GP2’s predecessor).

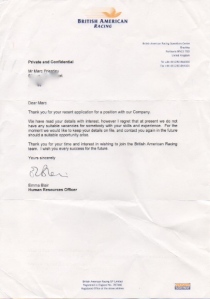

Eventually, by getting my CV onto the desk of McLaren’s test team manager through someone I’d met, I got myself noticed and amongst the steady stream of rejection letters landing on my doorstep from all quarters of my favourite sport, got an invite to come and meet him at the team’s factory.

Eventually, by getting my CV onto the desk of McLaren’s test team manager through someone I’d met, I got myself noticed and amongst the steady stream of rejection letters landing on my doorstep from all quarters of my favourite sport, got an invite to come and meet him at the team’s factory.

To say I was excited would be an understatement of epic proportions and as the day drew nearer, the excitement was rapidly overtaken by nerves.

I remember sitting in my car in McLaren’s old car park, about two hours early, so as not to be late, thinking how incredible it was just to be on the property. I was shaking at the prospect of walking through the doors of a place that I read about daily. Meeting people, who in my little world, were some of the most respected and revered, almost celebrity-like, characters in my life…and that was simply because of the place they worked and the shirt they wore.

The interview went well and I got to meet a number of key people and even got shown around the famous factory. I remember thinking if I didn’t get the job, I’d still die a happy man with that experience alone.

Weeks later I got the call that I’ll never ever forget and that changed my life forever…I was a Formula One mechanic at McLaren.

I didn’t just get given a new job, but a new family and an entirely new life. It’s a life that’s incredibly hard at times, requires a great deal of sacrifice and absolute dedication, but in return offers more than I  could’ve ever imagined.

could’ve ever imagined.

More than 15 years later, although no longer part of McLaren, I’m very lucky to still be part of the F1 family. I share the life with many of my best friends in the world and have been fortunate to enjoy and play a part in some amazing experiences.

My biggest piece of advice is to follow your dreams. If you’re passionate about working in motorsport, then be tenacious, grab hold of every opportunity and don’t let go until you get what you want. Opportunities rarely just appear, so create them for yourself.

It’s a wonderful world that offers things no other career can. Travel the world, meet friends for life, get the adrenaline rush, celebrate the good times and develop from the disappointments. It’s best not to try and work out your hourly pay rate at times, but know that you’ll never be bored or have that dreaded ‘Sunday night feeling’ of having to go back to work on a Monday morning.

It’s best not to try and work out your hourly pay rate at times, but know that you’ll never be bored or have that dreaded ‘Sunday night feeling’ of having to go back to work on a Monday morning.

Hopefully I’ll see some of you in the paddock before too long.

Marc Priestley

@f1elvis

Following another great Formula E event in Punta del Este, Uruguay, I thought I’d just unravel a couple of things that we didn’t get a chance to talk about in our live ITV4 show on Saturday. There’ve been a few drivers suffering penalties recently for various indiscretions, either by them or their teams, that I think need a little more explanation. In Malaysia a few weeks ago, we saw Jerome d’Ambrosio, or ‘Custard’ as he’s affectionately know in the paddock, get excluded from qualifying for “exceeding power usage”. There’s an important distinction to make here, which is the difference between ‘energy’ and ‘power’. In simple terms, energy is effectively the amount of work the battery can do, whilst power is the rate at which it’s asked do it. The drivers have a defined amount of usable energy (28kwh) in the race for each car, which is slightly less than the actual total capacity of the battery. The percentage figure you see on screen next to drivers names during the race is the percentage of usable energy each driver has left with that car, i.e. how much of his or her 28kwh. It’s up to the driver and their team to manage energy usage so as not to go over that limit. We saw Daniel Abt penalised for exceeding this figure in Beijing by a small amount.  Power’s measured in kw and the drivers have a ‘power map’ or torque control switch on the steering wheel with six settings available to adjust this. The regulations stipulate the maximum power for qualifying (200kw) and the race (150kw), with the temporary additional boost up to 180kw with Fanboost. In the race, drivers will change the power map setting to control their pace at different points and the rate at which they’re using up the 28kwh of useable energy. You can perhaps equate it to fuel flow in Formula One, where teams have a maximum of 100kgs of fuel for the race and can vary the rate at which they use it, through engine maps, but can’t go over a 100kgs/hour fuel flow limit. In qualifying however, they’re all naturally using maximum power (200kw) on their timed laps, so it begs the question, how is it possible to exceed this limit, when in theory the system can’t physically ever deliver any more power than this anyway? The answer’s not a particularly sophisticated one, but lies in the fact that teams program their own power maps into their cars and rely on ‘the system’ to keep it from spiking over the allowed limits. The steering wheel controlled maps are essentially bits of software code to tell the Williams battery how much power to deliver through the McLaren motor control unit into the eMotor itself. Because of various system tolerances and electrical losses, when a team writes a map to request 200kw, typically they may only see something around 190-195kw as a final output. It may only seem like a small amount, but it’s a performance differentiator, so teams write maps to demand a figure that’s just over the 200kw in qualifying and just over 150kw in the race and hope that both the McLaren and Williams software will catch any spikes and prevent them from breaching the legal limits. On a couple of occasions that hasn’t happened and the FIA data’s showed marginal, but none-the-less, excessive power usage and the result is an immediate penalty, as happened to d’Ambrosio. Teams would argue that the various systems on the car should be able to give them their maximum allowed power without the worry of going over it and you could perhaps see their point. The FIA and stewards however, would no doubt retort with the argument that if teams know there’s a risk when writing maps that demand more than their allowed maximum power, then they simply shouldn’t do it. Also back in Malaysia, Katherine Legge received a ten place grid penalty to be applied at the next event, for changing her RESS (Rechargeable Energy Storage System), or the car’s battery, after a failure. This is similar to the engine or gearbox change rules in Formula One where a component failure results in a grid drop penalty. She didn’t race in Uruguay, so rather than apply the penalty to her car, driven by Salvador Duran, it will apply to the next event she takes part in.

Power’s measured in kw and the drivers have a ‘power map’ or torque control switch on the steering wheel with six settings available to adjust this. The regulations stipulate the maximum power for qualifying (200kw) and the race (150kw), with the temporary additional boost up to 180kw with Fanboost. In the race, drivers will change the power map setting to control their pace at different points and the rate at which they’re using up the 28kwh of useable energy. You can perhaps equate it to fuel flow in Formula One, where teams have a maximum of 100kgs of fuel for the race and can vary the rate at which they use it, through engine maps, but can’t go over a 100kgs/hour fuel flow limit. In qualifying however, they’re all naturally using maximum power (200kw) on their timed laps, so it begs the question, how is it possible to exceed this limit, when in theory the system can’t physically ever deliver any more power than this anyway? The answer’s not a particularly sophisticated one, but lies in the fact that teams program their own power maps into their cars and rely on ‘the system’ to keep it from spiking over the allowed limits. The steering wheel controlled maps are essentially bits of software code to tell the Williams battery how much power to deliver through the McLaren motor control unit into the eMotor itself. Because of various system tolerances and electrical losses, when a team writes a map to request 200kw, typically they may only see something around 190-195kw as a final output. It may only seem like a small amount, but it’s a performance differentiator, so teams write maps to demand a figure that’s just over the 200kw in qualifying and just over 150kw in the race and hope that both the McLaren and Williams software will catch any spikes and prevent them from breaching the legal limits. On a couple of occasions that hasn’t happened and the FIA data’s showed marginal, but none-the-less, excessive power usage and the result is an immediate penalty, as happened to d’Ambrosio. Teams would argue that the various systems on the car should be able to give them their maximum allowed power without the worry of going over it and you could perhaps see their point. The FIA and stewards however, would no doubt retort with the argument that if teams know there’s a risk when writing maps that demand more than their allowed maximum power, then they simply shouldn’t do it. Also back in Malaysia, Katherine Legge received a ten place grid penalty to be applied at the next event, for changing her RESS (Rechargeable Energy Storage System), or the car’s battery, after a failure. This is similar to the engine or gearbox change rules in Formula One where a component failure results in a grid drop penalty. She didn’t race in Uruguay, so rather than apply the penalty to her car, driven by Salvador Duran, it will apply to the next event she takes part in. At the same race, Nick Heidfeld was penalised for not conducting his car swap in the designated area. That area is the team’s garage and on that occasion Nick crashed and returned to the garage on foot to take the second car. In Punta del Este this weekend, Bruno Senna was excluded from qualifying after his team breached a regulation that states all cars taking part are under parc ferme conditions from five minutes prior to the first qualifying group getting their green light. Parc ferme conditions stipulate that no work, other than temperature management, can be carried out on the cars during this period.

At the same race, Nick Heidfeld was penalised for not conducting his car swap in the designated area. That area is the team’s garage and on that occasion Nick crashed and returned to the garage on foot to take the second car. In Punta del Este this weekend, Bruno Senna was excluded from qualifying after his team breached a regulation that states all cars taking part are under parc ferme conditions from five minutes prior to the first qualifying group getting their green light. Parc ferme conditions stipulate that no work, other than temperature management, can be carried out on the cars during this period.

Marc Priestley @f1elvis

Check out my video explanations of the Williams Formula E battery and McLaren electric motor.

http://www.itv.com/formula-e/video-lifting-the-lid-on-formula-e-battery-technology#

http://www.itv.com/formula-e/video-lifting-the-lid-on-formula-e-battery-technology#

http://www.itv.com/formula-e/feature-how-the-electric-motor-works

There’s no doubt that Round Two of the FIA Formula E Championship provided some great racing, or that winner, Sam Bird, did a great job in dominating the race in seemingly comfortable fashion.

A closer look at some of the numbers however, gives a little bit more insight into a few of the strengths and weaknesses of the teams and drivers during the Putrajaya event.

Laptime on street circuits, through their unforgiving nature, is all about the driver building confidence throughout each session, gradually edging closer to the limits and learning where they can push and where they need to respect the kerbs and walls etc.

In traditional forms of racing, where a series visits street tracks, there may well be two days of practice sessions before it gets to raceday, allowing for that gradual progression as the drivers dial into their groove.

In Formula E however, the tight, compact, single day schedule means drivers need to be straight on the ball in free practice and can’t really afford to step over circuit limits and into the barriers. Not only do they lose valuable and rare track time, but there’s little opportunity for team mechanics to carry out major repairs, before qualifying or the race is upon them.

Without touching the unforgiving circuit walls, ultimate lap time does come from running mighty close to them, so a driver with confidence in himself and his car on any given circuit has a big advantage. Developing that confidence is the main priority in the first two practice sessions at each event.

Sam won the race through a combination of a decent qualifying lap, albeit two tenths down on eventual pole man Oriol Servia, and promotion after the disqualification of Jerome D’Ambrosio and Beijing carryover penalty for Nico Prost, together with experienced race craft and far superior energy management than anyone else on the grid.

The fact that his qualifying lap was around 7/10ths slower than he went in practice, perhaps says a bit about the more risk-averse approach to the vital qualifying session. His morning time would have actually been good enough for pole by some margin, but the consequences of getting it wrong, considerably more serious.

The race in Putrajaya really highlighted some of the intricacies of Formula E, compared to some other forms of racing.

The all out, blistering pace over one lap in qualifying requires something all together different than the controlled, intelligent and measured approach to the race itself and various teams excelled or struggled in different areas.

From disjointed and troubled beginnings, the two Dragon Racing cars of Servià and D’Ambrosio lead the way in qualifying, showing impressive single lap pace, although the latter was later disqualified for marginally exceeding the permitted power usage. Jarno Trulli too, was a surprise name at the sharp end of the grid, lining up on row two after failing to impress in testing or in Beijing.

If these teams are playing catch up, having been late starters when the series first took to the track at Donington, it perhaps showed in Malaysia.

A car that delivers ultimate lap time on a street circuit, perhaps in higher downforce specification, may not be the car to best manage the longevity of the race. Even more importantly, the approach to efficient driving in race mode is also vastly different to that required for a qualifying run.

With the super hard Formula E Michelins, tyre management isn’t so much of a concern in the race, meaning a low drag, low downforce set up will help to extend range without destroying rear tyres before switching to the second car. It does however require the driver to control the car without relying on downforce to help them.

After D’Ambrosio’s elimination, Servià and Trulli disappointed in the race lapping between 0.5 and 1.0sec slower on average than Virgin’s Sam Bird up front, who himself was merely pacing himself for much of the 31 lap eprix.

The really impressive race pace came from the group of pre-event-favourites in Prost, Senna, di Grassi and Buemi, who all found themselves out of ‘natural’ position on the grid for various reasons and yet progressed beyond most expectations in the race to be able to chase down Bird in the closing stages.

The small group managed to move up the field due to a number of incidents ahead of them, but also by moving together as a pack. They all bided their time, much like the peloton in a cycle race, using the tow from the cars in front to drag them forward. They managed their electrical energy well and stayed out, as a group, one lap longer than many around them, pitting on lap 18.

The two early safety cars took away much of the need for extreme energy conservation, but staying out for the extra lap, meant their second cars could run fast to the flag without needing to worry too much about running out of battery power. This impressive group all set their fastest laps in the last part of the race, reeling in cars which stopped earlier and were now having to think twice about using their full 150kw power maps.

For Bird, in front from the safety car restart, he had to focus on his own race and did a great job. After taking the lead he managed the gap well and did the same with the car’s battery.

Being out in front he controlled the pace and energy usage and had plenty in hand when everyone approached the pitstop window from lap 16 onwards.

As many began to stop on lap 17, Sam had good pace and one eye on the group he knew could cause a threat towards the end.

He circulated again, but being the first car round each lap had to decide before the others wether to stop or not. On lap 18 he continued, a move I considered a little risky at the time, for another lap.

The risk became more apparent when the chasing pack all stopped moments later for their second cars. Whilst Sam wasn’t in danger of losing track position on pace alone, the chance of safety cars in street races is high, we’d already seen two earlier in the race.

If someone had got out of shape in their ‘cold’ and relatively unfamiliar second car on an out lap and hit the wall, the race leader, the only man now not to have stopped, would’ve found himself languishing at the back of a very long train of cars once he finally did pit and the BMWi8 safety car returned to the pitlane.

As it turned out, he pitted a lap later, with the television graphic showing the car’s battery at 3% and returned unruffled to the front of the field, but the unnecessary risk was present nonetheless.

Whilst the tv battery percentage graphics need to be taken with something of a pinch of salt, it’s safe to say he wouldn’t have been able to go too much further, but with hindsight, on another day it could have caught the team out to great effect.

Marc Priestley

@f1elvis

I count myself incredibly lucky to have worked for a Formula One team and gone into the last day of a season with the chance of my driver emerging as World Champion, on three separate occasions.

On one of those memorable days, with Kimi in 2003, we went in as underdogs with only a slim chance of the outcome we so desperately wanted, similar to Nico Rosberg and his Mercedes crew in Abu Dhabi.

We needed, on that occasion, for our rivals to slip up, together with a great result for us, but sadly it wasn’t to be and Michael Schumacher, took the coveted crown.

In 2007, as a team we found ourselves in the rare but currently familiar situation of going into the last day of the campaign knowing either of our two drivers, Alonso and Hamilton, could be victorious with the right results. On that day however, a third man, the underdog in Kimi Raikkonen and his shiny new red Ferrari, would emerge as the new champion and we painfully missed out again.

2008 saw one of the sports most memorable finishes in Brazil and as a team, we once more walked into the circuit that day knowing we had an amazing opportunity, but once more felt the weight of expectation of millions of fans around the world, the heavy British Media presence and not least, the pressure we piled onto ourselves.

The reason for recalling these very special occasions is to try and describe my feelings on the day and in the days building up. To give some insight into the way the guys and girls at Mercedes might be feeling this weekend as they approach, what will be for many, the biggest day of their professional careers.

The thing to note about these situations is that it’s like the holy grail for a Formula One team. Just as a driver has dreamt of becoming World Champion since the first day he jumped into a junior racing car, the mechanics, engineers, designers, support crew and everyone inside the team are equally as passionate and dedicated about what they do and that title means just as much to them.

For me, that weekend in 2003 meant everything. We were a close-knit crew on Kimi’s car, had shared wonderful highs like our first win together in the Malaysian Grand Prix and suffered heart breaking lows like engine failure whilst comfortably leading the European GP.

Our chances on the day were statistically slim to say the least, but that didn’t matter to me, we had a chance and I was incredibly proud of that alone.

As it turned out, we did all we could, but the results will forever show that Michael scored two more points than we did and was Formula One World Champion. I was heartbroken.

Most people would say that Schumacher and Ferrari deserved the title that year, he had after all won six races to our one, just as Lewis has ten victories to Nico’s five today.

But to me eleven years ago, just as it’ll feel to the crew on Nico’s side of the garage in Abu Dhabi, it’s just the guy with most points at the end that deserves the title, not the manner in which they collected them.

The opportunity to even fight for a world championship is incredibly hard to achieve, so if and when that chance comes around, it means the world to those involved.

2007 was different. As a team we hadn’t won a championship since 1999 with Mika and if I’m honest it showed.

The internal fighting between teammates is well documented, but from a team point of view we allowed our focus to stray from the big picture of team success to concentrating too much on beating the other side of our own garage and not giving anything away to the ‘enemy’.

There was an odd atmosphere inside the team, a feeling of paranoia wherever you looked, both in terms of second guessing what the other half might do, but also that on this most important of days, the slightest mistake by any member of the team could swing the title either way.

We had the current World Champion in Fernando, who’s entire nation already hated the brits and blamed the team for his political difficulties that year, on one side.

On the other, Ron’s prodigy, the new poster boy of British sport with the my own nation willing him to win, in Lewis.

The individual pressure to succeed as a mechanic on days like this is big, but the pressure not to fail is far, far greater.

I remember feeling terrified that we’d missed something all the way through Sunday morning, something I’d never normally feel, as I was experienced, confident in my own ability. I’d prepared cars and guided young teams of mechanics through countless high pressure race days before, yet this one felt different.

We should’ve had a feeling of pride amongst the whole team, a morning of both sides of the garage wishing the other luck with team management doing the same.

Instead, when management did give their Sunday morning speech to the assembled crews, it had a feeling of the referee calling two fighters into the middle of a boxing ring to lay down the laws of the bout, before both sides retreated to their corners for a team huddle.

Of course that’s an exaggeration, but the sentiment’s the same. Instead of approaching the race weekend as we should, like any other, we raised the tension ourselves, led by our own two feuding drivers.

It’s when you begin to do anything differently to normal, that mistakes can creep in. We were all highly skilled, more than capable of doing our jobs, of preparing the cars, working with the drivers and engineers, delivering perfect pitstops and race strategy.

On a normal Sunday morning there would’ve been no doubt, we’d be relaxed, the car would be ready and we’d be watching the GP2 race on the garage screens ahead of the Grand Prix.

On this day however, there was fear throughout the team, I could see it on the faces of my team mates, I could see it in their behaviour, I could feel it myself.

When you get your car onto the grid on days like this, the job should be all but done. But as a mechanic, you look around the car, sat there with cooling fans in and tyre blankets on, computers plugged in etc and desperately look for a missing bolt or loose nut that you might have forgotten. If anything does go wrong today, more than anything you don’t want it to be your fault.

Experience gets you through these things, but for the younger guys at Mercedes, who’ve perhaps never been in this situation, it’s incredibly daunting.

Despite my extensive experience in 2008, by which time I was no longer working on the cars, but overseeing the guys who were, the pressure again was formidable.

We had only one driver to focus on this time around, but again we made strategic mistakes by approaching the race looking for the fifth place we needed for the title, rather than going out to win as we normally would.

As a result we came perilously close to letting it slip away and the emotional roller coaster we all went on that day I will never forget.

I’ve no doubt they will be trying to do just this, but Mercedes need to go into Abu Dhabi like they’ve gone into every other weekend of the year.

Focussing too much on each other, or on desperately making sure both get the same equal treatment, could mean the things they can normally do with their eyes closed, get overlooked.

Whatever happens may the best man, and his crew, win the title on Sunday, but the whole team should all be incredibly proud of what they’ve achieved.

Marc Priestley

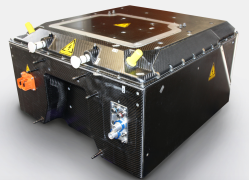

What exactly drives a Formula E car if it has no internal combustion engine? We know it’s battery powered, but what kind of battery? What does it look like? Where is it in the car and how does it compare to the batteries we know from around our homes?

I recently spent a morning with the clever folk of Williams Advanced Engineering, the division of the Williams Group that we all know and love for their Williams Formula One Team, that take knowledge and technology gained through F1 and develop it for use in other markets.

Williams is an impressive company. They, together with my old team McLaren, have led the way in diversifying from their core Formula One businesses and putting their impressive skills, knowledge base and competitive natures, together with the ‘can-do’ attitude prevalent in the very top level of open wheeled motorsport, to use across a variety of sectors.

Through five years of developing high end battery technology for Formula One’s KERS and now ERS programs, Williams Advanced Engineering were well placed to extend that know-how into meeting the unique demands of a fully electric race car battery.

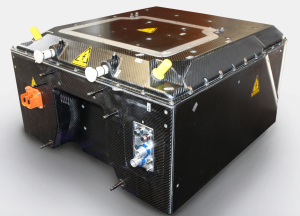

FE’s battery box. Weighing in at around 320kgs, containing cells connected in series, cooling system & electronic & thermal management system.

The Spark-Renault SRT_01E Formula E car was already well under way when Williams got the call and so the battery had to be designed to fit into a structural box, designed by chassis manufacturers, Dallara, and meeting the energy, power, weight and safety requirements mandated by the FIA.

The battery box, a large carbon fibre structure with bolt on lid, sits in the space most single seater racing cars use for the engine and fuel cell, just behind the driver.

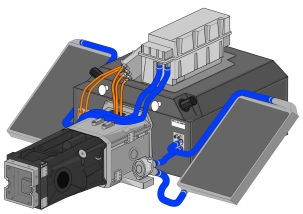

It’s what’s known as a ‘stressed member’ of the car and that means it bolts structurally directly to the back of the chassis or monocoque and transmits all of the torsional, or twisting, forces from front to rear and vice versa as the car’s on track. The electric motor housing and gearbox casing bolt directly to the back of the battery box, continuing the structural nature of the car’s main assemblies.

This is common practice and is the same basic layout as a Formula One car, just swapping the engine and clutch housing for the electric drive components in Formula E.

The large FE battery box, with electric motor housing & gearbox bolted to the rear, motor control unit on top and sidepod mounted radiators to each side. Drawing by @scarbsf1

This means designers are able to more efficiently control and utilise the loads going through the vehicle with suspension design, rather than having a flexible chassis, that twists and contorts over bumps and through corners, giving an unpredictable feel to the driver at racing speeds.

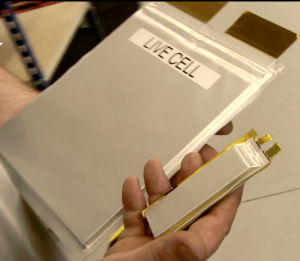

A large FE lithium-ion battery cell, here compared to a much smaller early F1 KERS cell

Lithium-ion batteries are nothing new, they’re what we all have in the back of our mobile phones and laptops, but whilst all part of the lithium-ion family of batteries, the cell chemistry is designed specifically for the needs of each application and that’s a closely guarded secret at Williams. With all those cells connected together in series, the FE battery is capable of delivering 200kw, or around 270hp.

An innovative cooling system is integrated into the battery box to help maintain stable temperatures across the entire unit.

A non-conductive fluid, known as a dielectric, is pumped around the inside of the battery case and around each cell, before being circulated through a traditional style, sidepod mounted, cooling radiator and back into the box.

As energy is transferred from the battery into the car’s electric motor at varying levels, depending on the driver controlled, steering wheel mounted map switch position and of course the accelerator pedal demand, the chemical reaction in the battery cells generates a considerable amount of heat.

Equally, during the rapid charging process with the cars in the garage, the reverse chemical reaction, transferring lithium ions in the opposite direction between one side of the cell and the other, also heats up the battery considerably.

With the car stationary inside the garage, powerful blowers and dry ice are used to cool the radiators and consequently the battery while it’s recharged, a process which takes around 45 minutes, but one that can only begin once the unit has been pre-conditioned, or brought into the optimum temperature window by the team.

Batteries have to be strictly maintained and their cell temperatures are carefully monitored at all times by a sophisticated battery management system (BMS), sitting inside the box on top of the cell modules. The system has the ability to shut down cells if required, or switch to a reduced power failsafe mode if things get a little too hot.

Williams have given detailed guidelines to the teams on how to operate the battery within its performance parameters, but are well aware that the competitive nature of motorsport means that they’ll always be looking to find ways to gain advantages through areas like the car’s regenerative system, or ‘regen’, over each race weekend.

Pushing too hard lap after lap will overheat cells, so efficient and strategic deployment of the energy available is absolutely crucial to performance in Formula E.

More than one driver in Beijing hit temperature limits, resulting in the system reducing power until normal levels were reached, so teams will be well aware that the high ambient temps in Malaysia need to be respected.

Williams engineers have also programmed new, slightly reduced, limits for the amounts of energy regenerated by the motor/generator unit under braking, that can be fed back into the battery whilst the cars are on track for the Putrajaya race. The reduction won’t cause any noticeable difference in the spectacle, but is simply an extra measure to make sure batteries maintain their performance under these tough conditions.

Looking towards the coming years of Formula E, it’s hoped competition will drive innovation, particularly in battery technology and electric motors as technical regulations are opened up to manufacturers.

Williams Advanced Engineering are already assessing a number of options, including the possibility of becoming an electric motor supplier, again utilising their expertise gained in F1 with ERS.

There are various battery development paths the series could take, ranging from increased power or energy density, to rapid charging or even battery swap technology, all of which will help to accelerate progress in the key areas of electrical energy storage and deployment, something Williams hope to be able to benefit from as they look to transfer their own learning into the automotive world and beyond.

Whilst it may be easy for the cynics to criticise the shortcomings of battery technology today, the opposing view and the one I hold, is that the battery we’re using in Formula E is already an incredibly advanced piece of kit, but the competitive nature of motorsport should help to push forward development much faster than in the ‘real world’.

I hope we might look back in a few years, using today as a benchmark and marvel at how the technology’s progressed, citing the fact that if Formula E and Williams Advanced Engineering hadn’t taken the plunge in 2014, we might never have got there at all.

Marc Priestley

You can catch me on this weekend’s ITV4 Formula E show, starting at 5am on Saturday, with highlights on the same day at 6pm.

Formula E burst into the spotlight recently with its inaugural race in Beijing, grabbing headlines around the world, at least partly due to the spectacular last lap crash between Nick Heidfeld and Nico Prost. I was privileged to be there in my broadcasting role for ITV and it felt like an important occasion, a significant event to be part of and an event worthy of its global coverage.

In truth though, the headlines were already being made long before the race even got underway and that was the result of a very deliberate and orchestrated marketing and media strategy by the series promoters, Formula E Holdings (FEH).

In the year building up to the first event, FEH drip fed the media with news, announcements of drivers and teams, venues and its plans for the fan experience.

Many of those deals were done long before they were released into the public domain, but the carefully staggered updates kept the new sport in the pages of the motorsport press and consequently in the minds of those who read such material.

As we approached Beijing, naturally hype grew and taking full advantage of Formula One’s enforced mid-season shutdown, FEH upped their media presence at a time when the biggest players in the traditional market were quietly sunning themselves on beaches, with F1 at the very back of their minds.

A new global marketing campaign was launched, entitled “Drive to the Future” and centred around a brand new television commercial; driver announcements and international broadcasting announcements; each accompanied by a host of ‘appearances’ and well placed social media interactions. News and footage of a full Formula E race simulation, including race start, appeared and one last official test day, open and free to the public, took place with an impressive and inquisitive attendance.

Formula E played a good game off track and despite not having turned a competitive wheel on it, built an ever growing wave of intrigue around the new championship.

By the time we headed out to China for Round One, it was almost impossible, whether a motorsport fan or otherwise, not to have at least heard of Formula E.

Alejandro Agag, CEO of series promotor FEH, spent a relentless few weeks on the campaign trail, a world he has experience of from a past life as a European MP. He appeared on news shows, technology shows, children’s shows, environmental shows and at business conferences, speaking enthusiastically and insightfully about his own show and some of the driving forces behind it.

He built a purposeful picture of interactive entertainment that would have kids enthralled; new age technology, with the promise of watching it morph before our very eyes into something life changing for us all; close, exciting racing in iconic and glamorous locations and all underpinned by an ambitious mission to save the planet. Who wouldn’t buy into that?

Formula E has a unique platform on which to sell itself. Credentials come from the motorsport world, already hugely familiar with global marketing, but specifically now the disruptive technology and sustainability elements to the project are opening a number of very interesting doors into new markets.

The variety of the company’s targeted approach to different media fields shows the spectrum of intended appeal of Formula E and the equally varied spectrum of channels in which to promote it.

From a business and marketing sense, a new audience means a entirely new world of opportunities and as promoters, FEH have done a pretty good job here, attracting relevant partners and sizeable investment.

What’s disappointed me and perhaps surprised me most, is that almost all the teams, bar one, maybe two, missed the chance to steal the moment, to build on the propitious foundations laid by the organisers and differentiate themselves from the field.

Most Formula E outfits are being run by existing race teams, of varying success in other disciplines. They’re used to competing in established championships like GP2, GP3 and Formula 3 etc, where drivers pay the bills and as such don’t have much, if any, bias towards a marketing strategy.

What the new formula offers everyone involved is a level playing field. A blank canvass on which to draw up a set of plans. There’s a huge opportunity to establish a brand, create a new identity and forge strategic B2B partnerships enabling vested parties to grow into something instantly recognisable. All on a platform fixed upon by the world’s eyes, yet still too infant-like to have divided itself up into the major players and the also-rans.

A blank canvass on which to draw up a set of plans. There’s a huge opportunity to establish a brand, create a new identity and forge strategic B2B partnerships enabling vested parties to grow into something instantly recognisable. All on a platform fixed upon by the world’s eyes, yet still too infant-like to have divided itself up into the major players and the also-rans.

The teams will all say they had too much on their plates in just being ready on a practical level for the first race, but surely it simply boils down to a matter of priorities?

If you’re the team that ends up as champions, then there’s your ticket, there’s a big part of your marketing plan written for you out on track. But only one team can capitalise on that and it’s a risky strategy that has to wait for race results before being put into action. If everyone takes that approach with prospective sponsors, nine out of the ten teams in Formula E will fail to deliver on their promises of success and likely fail to secure much investment in their futures.

The more shrewd tactic is to take advantage of the level playing field before the ‘on track’ winners are created.

With FEH having created such intrigue and excitement, on so many different channels, the chance for teams to create partnerships that would benefit them in a number of ways is huge.

Whilst none of the teams could target investors claiming to be the most successful Formula E team on the grid, or site their winning car as the premium advertising space ahead of Beijing, there are a number of other ways to successfully sell themselves.

In a field of ten new teams; close to identical in size and structure; in a new championship; with a new audience demographic on a global scale; the race to be number one, should’ve started long before cars hit the streets.

Formula E offers exposure in the traditional sense of large numbers of television consumers across many territories, it offers advertising opportunities to brands on the sides of race cars, drivers overalls, trackside billboards and everything that comes along with that. But with this project comes a new level of exposure on top of the traditional, an exposure that could be far more relevant and beneficial to the modern business world if utilised well.

FE teams have much more control at the moment over the amounts and type of content they release through their own digital channels, with fewer restrictions on audio and video based media and an embracement of platforms like Vine and Instagram. Social media isn’t just a bolt-on for Formula E, it’s an integral part of the strategy, something that the series has been built around and intends to thrive upon.

When almost every other motorsport discipline was created, social media didn’t even exist, so they’re having to try and integrate it into an already established model, something that some are finding easier than others.

When almost every other motorsport discipline was created, social media didn’t even exist, so they’re having to try and integrate it into an already established model, something that some are finding easier than others.

Like it or not we now live in a social media generation. Formula E’s younger audience have grown up with it, businesses, both large and small, are finding invaluable ways to make it work for them and it’s something that, together with mobile technologies, gives direct access to the palms of consumers hands.

Establish yourself as the most visible; the most active and interactive; the most customer centric Formula E team straight out of the box and you’re instantly the most recognisable brand emerging from an otherwise confusingly bland array of competitors. A brand that those looking for direction in who to follow on this exciting new journey, will feel naturally connected to and supportive of. A brand that wrestles market share away from the rest without even turning a wheel and there are clearly a variety of ways in which to monetise and capitalise if you’re the market leaders. It’s a strategy that’s self perpetuating in its success, yet one that costs little more than a creative mind to initiate.

Sell that prospect, that ‘opportunity’ to a big and deliberately targeted ‘title sponsor’ and tap into their infrastructure, their expertise in marketing, their relevant technologies and their own network of consumers to benefit them and the team alike.

Form a partnership that can benefit both parties, allow the team to focus more on the racing and let the creative marketing experts do what they do best. Share and transfer knowledge in both directions and use the numerous channels Formula E offers, to shout from the rooftops about the excitement of the racing; the personalities and profiles of the drivers; the cutting edge technology and how its development will benefit us all in our road cars. Capitalise on the environmental benefits and the health benefits in city centres, there can’t be too many companies today that wouldn’t love to have that string to their bow.

Most of all, be creative, be inventive, do something that no-one’s done before and offer consumers a new experience. Make them feel part of the team and make your team stand out in the crowd. Use social media to create and share the type of content that Formula One isn’t able to offer because of its restrictive model.

Build a loyal fan base.

Whatever people think of FanBoost in Formula E, the idea that fans vote for their favourite drivers online, giving the most popular three a short power boost in the race, it’s a opportunity for teams to gain a performance advantage for free and, according to Agag, it’s here to stay.

Whatever people think of FanBoost in Formula E, the idea that fans vote for their favourite drivers online, giving the most popular three a short power boost in the race, it’s a opportunity for teams to gain a performance advantage for free and, according to Agag, it’s here to stay.

F1 teams spend millions looking for ways to shave off a tenth of a second a lap with their cars, yet FE teams have the chance of a significant speed differentiator and all they have to do to get it is campaign in whatever ingenious ways they can dream up for public support.

It’s surprising then, that very few have have taken up this new challenge to any significant degree.

Some teams were naturally more successful than others on track in Beijing, but it’s just as interesting to me how the correlation between Round One results, column inches and social media interactions don’t necessarily follow suit.

If we assume most teams are looking to be in this for the medium to long term, modern tradition would suggest success in the business sense, off track, is more likely to help secure success on it in the end and that looks like never being more true a sentiment than right now in Formula E.

Marc Priestley

@f1elvis

Car unreliability in Formula One can be caused by a number of different things.

Poor, or fragile initial design can obviously lead to a higher risk of component failure on the cars during their often extreme duty cycles in racing conditions.

Manufacturing faults, or the use of imperfect materials can equally be at the heart of mechanical breakdowns on the race track, where parts simply can’t cope with the stresses and strains thrust upon them on a Sunday afternoon.

Operational misuse is another common area for failure. Pushing parts of the car too far, pushing the people operating the car too far, or trying to do too much with the technology to hand is more common than many might realise and stems largely from the highly competitive nature of those people involved in our sport.

Of course with all of the sophistication, technology and analytical tools in Formula One, failures are far rarer than we’ve seen in years gone by, but one thing that can be very difficult to mitigate against, is the inevitable human element of the process and the occasional costly ‘mistakes’ that that can bring with it. No matter how professional a team is, no one’s immune to a very occasional slip-up.

Often these kind of errors, whether they’re bad strategic decisions, driver mistakes, detrimental setup choices, or ‘finger trouble’ from mechanics or system engineers, will often be explained away as technical failures by the team, but the reality is often that, while many would love to engineer F1 into an exact science, there are humans involved in all procedures…and humans make mistakes.

The 2014 season began with many predicting a disastrous race of attrition at the season opener in Australia. The vastly new technology was incredibly complex and difficult to package effectively, let alone to learn how to best use it for a performance advantage.

Pre-season testing had seen huge numbers of cars either stopping on circuit or being confined to the garages while solutions were sought for the technical issues being encountered. Some even openly questioned race director Charlie Whiting on exactly what he would do, should so many cars fail to finish in Australia that there weren’t enough competitors left to fill all of the points scoring positions.

The doomsayers were proved to be far from accurate with their pessimistic predictions and the first season of Formula One’s hybrid era has provided some wonderful entertainment. More than that though, the teams in F1’s pitlane should be highly commended for their adaptation and integration of the new technology under some pretty intense timescales and unimaginable pressure to succeed. Some difficult decisions had to be taken ahead of that first race in order to balance risk against reward, both for the individual teams themselves and for the good of the overall sport and its public perception.

Over half of the field breaking down in Australia would’ve done little to impress the watching millions, it would’ve done nothing to highlight the advantages of motor manufacturers being involved in our sport and showcasing their products and it would’ve done nothing but harm the championship ambitions of those taking part. Consequently, a number of teams had to reign back their performance in order to ensure adequate cooling, drivability, or longevity of their preciously fragile power units throughout the early races.

It’s perhaps a little surprising then, that the one team with such a dominant performance advantage over everyone else also has one of the most catastrophic reliability records.

Mercedes have come up with a car and power unit package that stands head and shoulders above all others, even up to 2 seconds a lap at some circuits. That’s meant they haven’t had to develop to the same level as some of their rivals and they’ve even been able to hold back on a number of upgrades throughout the season, simply because they haven’t needed them.

One might naturally think, that if a huge team with the resources of Mercedes was in the fortunate position of having a car that didn’t need to go much faster, they’d be diverting considerable chunks of time and budget into making it virtually ‘bullet proof’ in terms of reliability.

The truth is that they are. The team have stressed repeatedly that giving their two championship contenders tools to do their jobs is at the very top of their priority list right now and has been all year. There’s a ‘Reliability Team’ at Brackley, who’s sole purpose is to ensure quality control, designers will undoubtedly have a risk averse approach to new parts and updates and those working with the car in the field must be bordering on paranoia, wondering if the next failure will be down to them.

Surely getting through each race untroubled is on everyone’s minds right now and despite all of that, Nico Rosberg’s car failed disastrously in Singapore, because someone in the wider team at Mercedes didn’t do their job properly.

It wasn’t that a part broke, that its design was flawed or that it was being pushed beyond its normal limits. It wasn’t the result of Nico mistreating his car or that it had been in service for too long, it was simply that someone, most likely either in the electronics department or beyond that, the inspection department, had slipped up.

The official line is that “the steering column electronic circuits were contaminated with a foreign substance”, but what that almost certainly means is that whoever last took the column apart to inspect and service it, failed to clean it properly, or re-assemble it carefully enough afterwards. The substance could’ve been any number of cleaning sprays or substances, perhaps they were using one that, when left in contact for prolonged periods (ie. not cleaned off) eroded wiring or electronic components. Perhaps there had been some work done to the column itself and carbon fibre dust or particles were present, forming a conductive build up around components?

We don’t know exactly, but what’s certain is that, with the minuscule size of the circuit terminals and wiring in those areas of the car, it wouldn’t take very much at all to cause an intermittent short circuit like the one we saw in Singapore.

What’s almost unbelievable, but in truth just incredibly bad luck, is that by the time the problem manifested itself, it was too late to be able to do anything at all about it.

Whilst the team have been refreshingly open about the issue, providing at least some reasonable explanation of why Nico suffered the excruciating trauma we all watched him go through last week, they naturally haven’t gone as far as to apportion blame.

The reality is that there’ll be someone inside the factory at Brackley who’s feeling pretty low, knowing that they simply slipped up, but that that slip up proved very costly indeed.

Given that the perceived unreliability issues have somewhat evened themselves out between Hamilton and Rosberg and points are almost all square with five races to go, the pressure’s not only on the two guys in the driving seats. The entire team will be increasingly nervous that the forthcoming ‘five race Formula One World Championship’ could just as easily be decided by a simple oversight from any one of them, as it could by the outstanding talents of Lewis or Nico. Let’s hope not.

Marc Priestley

@f1elvis

Originally published at http://www.f1times.co.uk

The Belgian GP at Spa Francorchamps has always produced some thrilling races, overtaking moves and talking points, but this time around the post race media frenzy has reached staggering new levels.

A truly brilliant win for underdog, Daniel Ricciardo, has been hugely overshadowed by the events at Mercedes, but I suspect he, along with his Red Bull team, might be more than happy to take a back seat whilst the world focuses on the apparent impending self destruction of the World Champions elect.

It’s a situation I’m not unfamiliar with myself, having been in the McLaren garage during the tumultuous year of 2007, when relations between then teammates, Hamilton and Alonso, broke down completely during a season in which we enjoyed the rare luxury of having the dominant F1 car of the field.

Then, as now, the season began with smiles and mutual appreciation between the two, until it became clear that both drivers were equally matched in the car and both looked in with a genuine shout of the coveted Formula One World Championship title.

That title is the holy grail for F1 drivers, it’s the life long dream and something that the opportunity to grasp, presents itself to very few and on extremely rare occasions. It’s inevitable that, given a sniff of a chance, they’ll chase it with everything they have and won’t let go until they’ve got it. It’s probably the same philosophy that got most of them into F1 in the first place, but something that has very different implications in the sport’s premiere category.

In Formula Ford, Formula 3, GP2 or 3, or whatever else, the drivers are solely out for themselves and it’s the accepted way of the world. The cars, no matter if they’re from the same team or not, are all painted in individual liveries with their own personal sponsors and branding. The driver’s sole goal is to further his or her own career and more often than not, make it to F1. There is no such thing as a team order.

Effectively, in these lower categories, the race teams are being employed by the driver to provide them with a race winning car. That driver, their dad, or their sponsor (often their dad’s company or an associate) are paying the team huge sums of money, often their sole source of income, and as a result, teams are often left in a difficult position when it comes to imposing instructions on their drivers. They know they need to keep drivers happy, or the money disappears.

In F1, in the most part anyway, it works the other way. The teams hold many of the cards. At the front of the grid, they employ drivers on huge salaries, multi-year contracts tie them into global marketing campaigns and they become the next bit-part players in the sport’s Goliath-style heavyweight players. Many of the teams hold huge historical importance within F1 and are often owned by some of the worlds largest companies…the feeling is that no driver is bigger than the team and that they should essentially do as they’re told.

At the back end of the field, although a different financial situation, we still end up with the teams in the driving seat, so to speak.

Even though they may not have the wealth to pay huge wages, the historical success, or the corporate might enjoyed by some, they do still have a trump card to hold over the drivers in their cars. The F1 dream can only be realised if an opportunity to actually get into one of the 22 cars on the grid comes up. With hundreds of hopefuls working their way through the lower formulae trying to get there, the Marussia’s and Caterham’s of this F1 world, still have a large queue of youngsters desperate to do whatever is asked of them to get the chance. They may have to bring huge sponsorship packages with them, but they know if they don’t impress the team, there’s someone else waiting to pay for their seat.

The upshot of all this, is that the role of being a racing driver changes dramatically when you finally make it to Formula One, even though the determination, passion and desire for personal success doesn’t.

Every driver wants to win, no one wants to settle for second, although in this sport that’s exactly what can be asked of you by your team in certain circumstances.

As a driver, if you see a gap, even half a gap that might give you a chance of a win, or even more so, a World Championship, you want to be able to go for it, no matter who it’s against.

As a Formula One team however, the very last thing you want to see is your two drivers crashing into each other in a race. It goes against everything the hundreds of people within that team have worked towards, destroys your constructors championship challenge and can have huge negative impacts on the team’s marketing strategy. So you give clear instructions to your drivers to race hard and fair, but under no circumstances hit each other.

Nico Rosberg undoubtedly made an error of judgement in Spa that went down as a racing incident by the stewards. There aren’t many neutrals who would’ve liked to see either driver punished, least of all Lewis, but it would have surely been better for Nico if he’d just accepted he got it wrong, albeit in a racing incident and that he was just showing the sort of determination that Lewis has shown on so many occasions before.

When Hamilton drove through the field in Germany, colliding with three cars on the way in optimistic overtaking lunges, he and his rivals all escaped with minimal damage, but only through luck, way more than any form of considered judgement.

Some say the difference here is that it was team mates that crashed into each other, but the truth is that for both Lewis and Nico, they are no longer ‘team mates’, neither has even the slightest concern for the other’s fortunes and they’re the fiercest of all rivals out on track. There’s only one person most likely to stop either becoming World Champion and that’s the other one, so why would you not want to get past, wether it be lap 2 or lap 44?

The team, like in 2007, have a very difficult situation to deal with and they’d do well to remember that then, as now, there’s a guy not too far back, just waiting to steal the crown from the two squabbling ‘team mates’.

Marc Priestley

@f1elvis